How is it calculated?

To measure GDP each quarter, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) collects data from thousands of companies in the UK. And to complicate matters, there are three ways to measure it:

- the total value of goods and services (output) produced

- everyone in the country’s income

- or what everyone in the country has spent

As this ONS guide to measuring GDP explains, these are three ways to estimate the same thing. You get different figures depending on which method you use because there is never enough data to build a picture of the economy that is 100% complete.

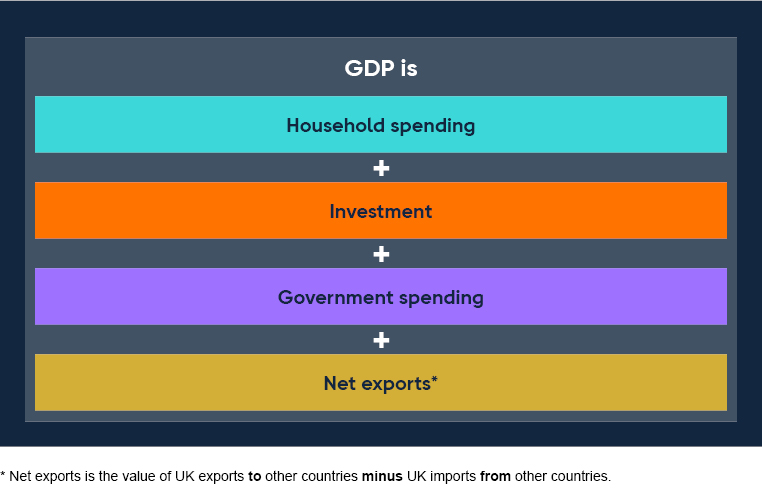

The last one – total spending – is perhaps the most familiar and can be broken down as:

Household spending forms the biggest part, accounting for about two thirds of GDP. Meanwhile, a business buying equipment or a construction company building houses are examples of investment.

So, when we talk about a country’s ‘output’, ‘expenditure’ or ‘income’, these are all ways to measure GDP.

For the above reason, GDP growth – also called ‘economic growth’ or just ‘growth’ – is a key measure of the overall strength of the economy.

Falling GDP often comes with falling incomes, lower spending and job cuts – which all lead to lower quality of life. If GDP falls during two consecutive quarters, this means the economy is in recession.

What is not covered in GDP statistics?

GDP growth is not the be all and end all of gauging how well an economy is doing.

To begin with, some things have a lot of value but are not captured in GDP because no money changes hands. Caring for an elderly relative would be one example of this. As the saying goes: ‘Not all that can be counted counts.’

GDP also does not tell us anything about how evenly income is split across the population. Growth could mean everyone becoming better off or just the richest segment getting even richer. In reality, it usually lies somewhere between the two.

Next, it helps to bear in mind changes in the size of the population. If the UK’s GDP rose by 2% next year, but the population grew by 4%, then average income per person actually would have fallen.

Finally, there are things that raise GDP but do not make the country better off. War is one example (a lot of money is spent, so GDP goes up). Or if a large chunk of the Amazon rainforest was cut down in one week, then you would get a sharp rise in GDP from the sales of timber but at huge environmental cost.

What are wider measures of wellbeing?

Because GDP is only one measure of the health of the economy, the ONS also collects data on broader measures of personal and societal wellbeing.

These include areas such as health, relationships, education and skills, what we do, where we live, our finances and the environment.

Other organisations consider different metrics of wellbeing and happiness. For instance, The Happy Planet Index (produced by the New Economic Foundation) measures whether nations are providing long, happy and sustainable lives for their citizens.

Find out more about how the ONS measures wellbeing

Find out more about the Happy Planet Index