Every day bundles of fresh banknotes land on the conveyor belts in our printing facility in Essex. The new cash is bought by wholesale distributors who supply to commercial banks, which stock some of it in ATMs all across the country.

Most of the money we print is to replace old, worn-out banknotes. But we also have to predict, or forecast, how much we think demand for cash will increase.

When forecasting demand for banknotes we have to think about what drives it.

Fundamental changes to society such as an increasing population, inflation and economic growth are important. We expect people to demand more banknotes over time because wages increase and things get more expensive.

We also know people want more notes when the economy is doing well because they have more money to spend.

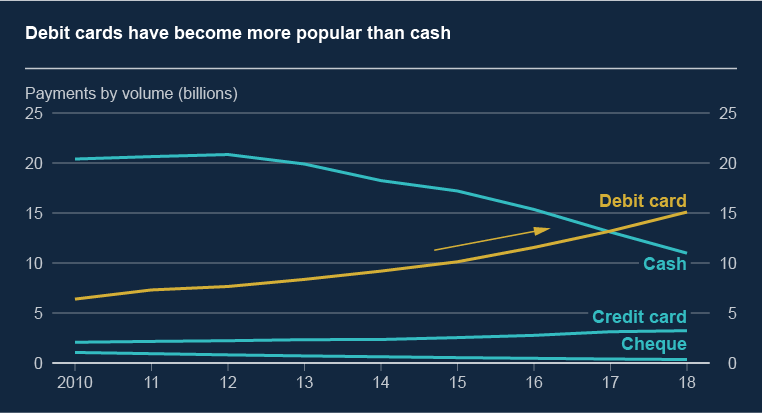

However, over time, technological developments such as the introduction of contactless cards means that less of this money is spent via cash.

When the pound drops in value, overseas demand for notes increases in part because overseas investors buy cash expecting to make a profit in the future. Tourists who need to exchange money ahead of their travels also tend to do so while it’s cheap. Overall, Britain becomes cheaper as a holiday destination and attracts more visitors when the pound goes down.

When the interest rate goes up, fewer people keep cash at home because it’s more lucrative to deposit money in the bank.

When we introduce a new series of notes we have to print many more new notes. In fact, we printed just over one billion notes ahead of the new £10 launch.

When do people want cash?

There are certain points in the year when you spend more. We print more cash to meet the extra demand at these times.

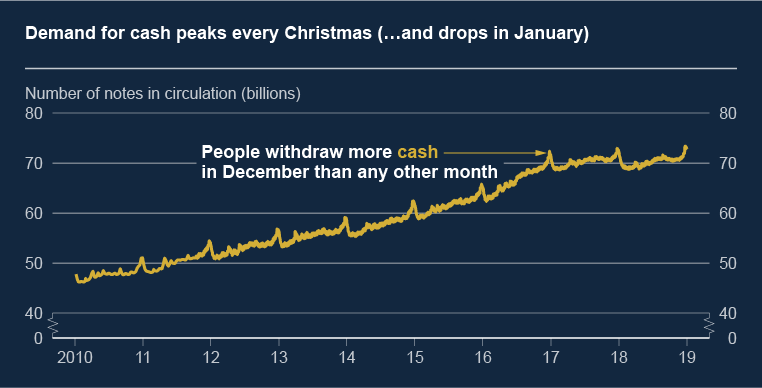

Recognising patterns in the demand for cash allow us to forecast when to print more banknotes. A good example of this is Christmas.

Whether you’re buying presents for family or train tickets home, it’s likely you spend more during the festive season (our explainer 'How much do we spend at Christmas?' shows how much more).

Each year in the run-up to Christmas, demand for cash reaches a peak.

How has demand for cash changed over time?

Over the past decades, demand for cash has grown, with the value of notes in the economy more than doubling since 2005. There has also been a fall in the use of cash in everyday spending.

In 2006, more than 60% of all payments were made in cash. In 2018, this dropped to 28%. This suggests more people are using cash as a store of value. For example, people may be hoarding notes at home as a way of saving, rather than using it to pay for things.

There are now signs the value of banknotes in the economy is stabilising. The demand for cash is usually highest in the run-up to Christmas, but in 2017 and 2018 growth was less than 1%. This might reflect a decrease in people using cash to pay for things, for the first time.

We can’t trace cash and so it’s impossible for us to know exactly what drives demand, but it may be that:

- Cash is a useful budgeting tool. Cash (compared to other payment methods, such as contactless) is tangible, which makes it easier to keep track of how much you are spending.

- There is a demand for Sterling cash overseas.

- Some people don’t put their money in the bank. Low interest rates incentivise increased hoarding, so notes remain in people’s wallets and shop tills for longer.

- Some cash may be used in the shadow economy, where activity is unrecorded and may be illegal.

- People like having cash in case of an emergency or if their local ATM goes out of service.

We’re the only issuer of Bank of England notes so it’s important we provide good quality notes which are difficult to counterfeit, in the amounts demanded by the public.